Dirk Stanley, MD, CMIO, UCoon Health

Hi fellow CMIOs, CNIOs, and other Applied Clinical Informatics and #HealthIT friends,

Today I thought I’d share the first ten (of 20) strong suggestions I put together into slides for other Applied Clinical Informaticists, or those considering a career in the field. I’m hoping this helps shed light on the importance and value of this role in modern healthcare, and how it helps to evaluate, implement, and maintain clinical technology and content.

First, my number one piece of advice to newcomers: Always map the current-state and future-state workflows. While some might argue this is an unnecessary step, this exercise will benefit you in some very important ways:

- It will help you understand and relate to your end-users.

- It will help you determine just how much work it takes to get from your current state (Point A) to your future state (Point B), which is necessary to help plan and allocate resources.

- It will help you develop blueprints, develop downtime forms, identify stakeholders, and scope/prioritize your projects.

For my second recommendation, I’d like to share how to write a good task, and then a good procedure. Learning to write a good task and procedure is so instrumental in building or untangling workflows, that it can even be used as a quick substitute for swim-lane diagrams (e.g., when trying to quickly document a workflow during a video chat with clinical end-users).

Recommendation number 3 involves something that sounds dull, until you learn about how it impacts your infrastructure and operations: document management. Learning how to create, edit, and archive documents can actually be a very powerful way of shaping or augmenting workflows in your electronic medical record. My mantra for newcomers: “Learn to control your documents, before they control you.”

My next recommendation (number four) is to learn the basic structure of healthcare operations by understanding the relationship between Administrative, Academic, Research, and Clinical Enterprises (Note: smaller community hospitals typically only have Academic and Clinical enterprises.)

In short, Administration supports the needs of the Academic, Research, and Clinical Enterprises. Learning how to navigate the people in these areas will help you break down silos, untangle workflows, and improve collaboration.

Coming in at number five is my recommendation to care about hard work, details, and precision. “In healthcare, there are no shortcuts.” While timelines are short, and there is often pressure to move ahead, try to resist the temptation to serve workflows that are not complete. (They may get you across the project finish line, but you risk having to do the whole project again — especially if end-users are not satisfied with the results.)

Recommendation number six might come as a surprise to some: When working in a team, file-naming conventions really matter. Group files should be both easy-to-find and easy-to-identify. My own personal favorite:

DRAFT/FINAL – ARCHETYPE – Descriptor – Created/Updated/Approved mm-dd-yyyy.ext

To offer some clarification:

- DRAFT/FINAL = Use ‘draft’ for documents in development, and ‘final’ when approved

- ARCHETYPE = Describes the file type (e.g. Education, Budget, Order Set, Catalog, Index, Contract, Policy, Protocol, Guideline, Schedule, Bylaws, Notes, Slide, Screenshot, etc.)

- Descriptor = Describes a unique identifier for the file (e.g., “ICU DKA Treatment Discussion”, “Meeting with Dr. Smith”, “Malaria Workup”, etc.)

- Created/Updated/Approved = Use ‘created’ when first creating a file, ‘updated’ when updating a file, and ‘approved’ when creating a final version

- mm-dd-yyyy = Describes when the file was created, updated, or approved

- ext = File extension (e.g., “.docx” or “.PDF”, etc.)

My next recommendation (number 7) is to learn the 24 basic tools that shape all clinical workflows: 12 are typically outside of the EMR, and the other 12 are found inside of it. Understanding the basic functions and design of each of these tools will help you to better plan projects, identify deliverables, identify stakeholders, and create smooth, complete clinical workflows.

Coming in at number eight is my general recommendation to all Applied Clinical Informaticists to care about the entire ‘Informatics tree’, including both the ‘Data In’ and ‘Data Out’ branches. While most people will gravitate toward one area, understanding the whole tree will broaden your perspectives and skill sets, and overall help you plan workflows.

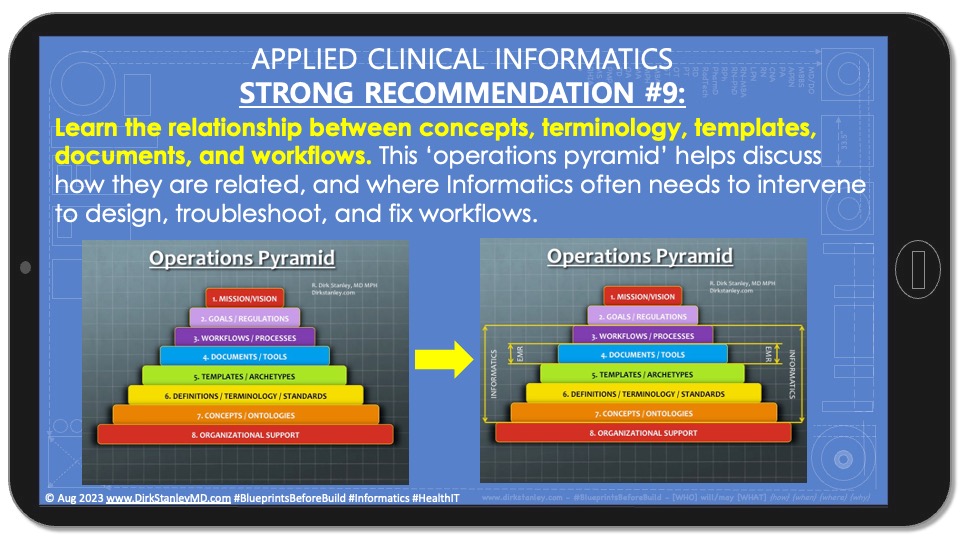

My ninth recommendation for Applied Clinical Informaticists seeking to design smooth workflows comes from this 2015 blog post, where I talked about the importance of learning the relationship between concepts, terminology, templates, documents, and workflows.

Organizational Support (#8) is necessary to:

- Identify the concepts and ontologies (#7) that help you…

- Develop the definitions, terminology, and standards (#6) that you need to…

- Develop the templates and archetypes (#5) that will help you…

- Create the documents and tools (#4) that, combined, will help to…

- Create and support the workflows and processes (#3) that, if designed properly, will…

- Align with your goals and regulations (#2) which should…

- Align with your Mission and Vision (#1).

Typically, after first understanding #2, Applied Clinical Informaticists will concern themselves with aligning levels #7 to #3 of this pyramid. (Learning how pyramid levels #8-5 impact the documents in #4 can help you troubleshoot even the most complicated workflows in #3.)

Finally, my tenth recommendation for Applied Clinical Informaticists seeking to design smooth workflow is to care deeply about change management. While Kotter’s 8-step change management model is an excellent foundation, I recommend beginning with a standard, linear waterfall project model and then expanding it slightly for healthcare purposes, to include the following:

- Conception, Determination, and Documentation of Need for Change

- Evaluation, Analysis, Scoping, Presentation, Prioritization, and Approval for Change

- Project Planning

- Drafting of Change

- Building of Change

- Testing of Change

- Final Approval of Change (go/no-go discussion)

- Communication and Education of Change

- Implication/Publication (‘Go-Live’) of Change

- Monitoring and Support of Change

Once these ten steps are laid out, you can begin looking at the tasks beneath each step and developing your own ‘waterfall-meets-healthcare’-type change management strategy.

I hope this set of slides is helpful. Feel free to leave comments below with any thoughts or feedback. In my next post, we will look at another 10 of my strong recommendations for Applied Clinical Informaticists seeking to design smooth workflows.

This piece was written Dirk Stanley, MD, a board-certified hospitalist, informaticist, workflow designer, and CMIO, on his blog, CMIO Perspective.